Alan Rode, senior staff writer for Filmmonthly.com sat down with Film Noir Foundation president Eddie Muller in late 2005 to discuss the mission and progress of the newly-formed non-profit corporation. Muller, noted novelist and film noir expert, and author of Dark City: The Lost World of Film Noir, Dark City Dames and The Art of Noir recently wrapped up his seventh year hosting and co programming the American Cinematheque’s Annual Festival of Film Noir in Hollywood. The “Czar of Noir” was clearly in an ebullient mood over the success of his two 2005 noir film festivals and recent events concerning the Film Noir Foundation.

A.R. The Film Noir Foundation is approaching its first year of existence. For those who may be unfamiliar with the Foundation, could you summarize the mission?

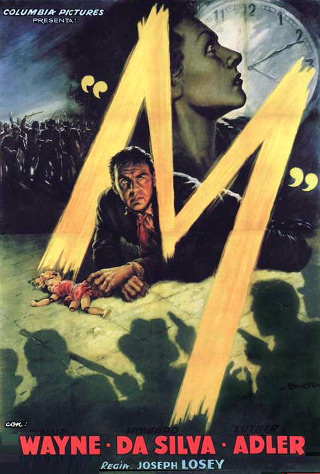

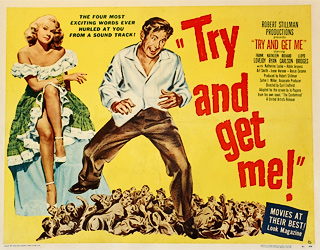

E.M. The Foundation was created when I realized a non-profit could get access to film archives that were off-limits to most for-profit theaters. In all honesty, that was the original impetus. I wanted people to see certain hard-to-find movies on the big screen, like Losey’s M and Try and Get Me. After a few years programming festivals, it also became obvious that there was an opportunity to sharpen the studios’ focus as to what they had in their vaults, and convince them there was some commercial viability in those films.

A.R. So, what is the Foundation’s specific plan with regard to film preservation?

E.M. The goal is to ensure that 35mm prints exist of virtually everything from the classic noir era. One of the few things I still believe in is the magic of the movies — and that magic is happening less and less in theaters, as we want to ensure that people can still have that experience with a vintage classic. Seeing a movie in a theater, with other people, offers you an altered state of consciousness. You were there when we showed Larceny at the Egyptian this past April . . . you know that the wonderful sense of discovery, or RE-discovery, wouldn’t be the same if you were watching it at home and pausing it to answer the phone. So the mission is two-fold: preserve the films, and find theatrical venues that make showing them again possible — because that’s how we’ll get new prints struck.

A.R. I think that many film purists and hard-core noir addicts might not understand that financial profitability and film preservation are inexorably linked. Could you elaborate on how this process works?

E.M. Film studios have little interest in altruism. They are in business for one reason: to make money. Their film libraries should be pure profit centers. But it costs a lot of dough to warehouse millions of miles of film — if they can figure out how to exploit 50 year-old movies, they’re heroes. If, purely out of the movie-loving goodness of their hearts, they requisition new prints of obscure movies that never get screened — they’ll probably get fired. So the Foundation’s job is helping them ferret out the rare stuff and getting it back in circulation. If a studio knows it can get 8-10 bookings of a certain film, that’ll pay for a new print. Compared to the home entertainment market, the money is a drop in the bucket, but it takes an organization like the Film Noir Foundation to draw attention to more marginal films, and help build a market for them. If we’re lucky, those films might end up being reissued on DVD, as well.

A.R. Are the studios fully aware of what resides in their vaults? How do they keep track of what they have and monitor the condition of film elements to ensure their care and preservation?

E.M. Most of them have great people working as vault keepers, like Bob O’Neil at Paramount, whose title is VP of Image Assets and Preservation. He wants to make new prints, and we have to compete for a share of that limited budget. I had meetings in April with all the major studios to introduce them to the Foundation. Having Anita Monga on the Advisory Council is a huge advantage. She got us all those meetings. The studios recognize her as one of the most savvy and successful repertory bookers in the country. [She booked the Castro Theatre in San Francisco for almost 20 years.] By and large, I was impressed with how cooperative and enthusiastic the studios were.

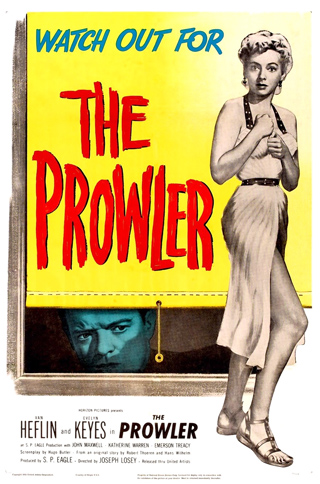

In the past, there have been some difficulties plumbing the archives, and getting accurate info on the status of certain titles. That’s changing. Frankly, I think the DVD revolution has a lot to do with it. It’s breeding a younger audience that’s really knowledgeable, and if they’re lucky enough to be in the right city, with the right venue, the chances are increasing that they can see film noir – even really rare titles — as they were meant to be seen: 35mm prints, on a big screen. Despite years of talk about the demise of single-screen movie theaters, we are seeing, in certain markets, a revival of the classic movie going experience. The Golden State Theatre just reopened in Monterey, California, converted from a triplex back to a single-screen, 600-seat venue. I’m doing a show there in June with James Ellroy, showing The Prowler, his favorite film. See, there’s a title that’s begging for a fresh 35mm print.

A.R. So what are “lost” films? Are they just misplaced or unavailable or merely inaccessible because somebody doesn’t want to go look for it?

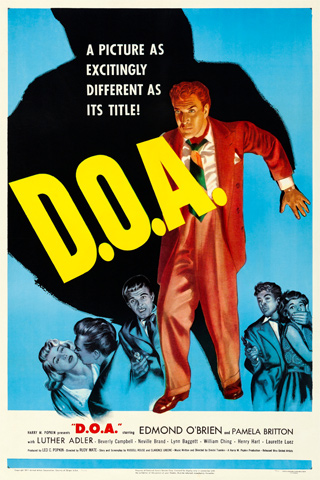

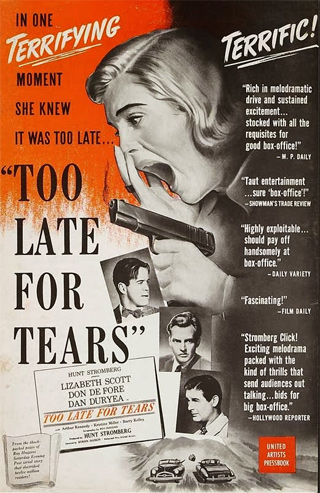

E.M. Ironically, the films in gravest danger of being lost, at least theatrically, are the ones that have slipped into the public domain; titles like D.O.A., Too Late for Tears, The Strange Love of Martha Ivers – 35s are virtually non-existent, and the 16s that are around are pretty beat. Some of them have been cleaned up for the bargain DVD releases that are glutting the low end of the market – but that doesn’t mean there’s a copy that can be shown theatrically.

In other cases, films become “lost” because there’s nobody who cares enough to run it down. The Prowler is a great example. Crystal Pictures has the only print in circulation. It was produced independently by Horizon Pictures, and distributed through United Artists. The original elements have to be tracked down if a new print is ever to be struck, and that means convincing whoever has those elements — which may not be the rights holder — that it’s worth the trouble. A big part of the Foundation’s mission will be getting disparate entities to work together to rescue a film. It’s not that difficult, really. You just have to be in a position to focus the searchlight. [Original elements for The Prowler recently turned up at a film exchange in France, and are now in the possession of the UCLA Film and Television Archive, which will work with the Film Noir Foundation to fund a restoration].

A.R. How real is the possibility of a film just rotting away?

E.M. If it’s a pre-1950s title, and the safety print has been lost or damaged, and the nitrate print isn’t in a proper archive, it could happen. The Eagle-Lion stuff is problematic, as is Film Classics stuff like Guilty Bystander. We had a really good talk with the UCLA Film & Television Archive about partnering to make restored prints of some of the titles they have in inventory. Off the top of my head, I can tell you that just within the last month we’ve located 35mm elements for The Chase, Night Has a Thousand Eyes, No Man of Her Own, Street of Chance (all Cornell Woolrich films), Among the Living, Red Light, The Man Who Cheated Himself, and Repeat Performance. Some of those only exist now in 16mm television prints, others do not exist at all. Yet.

A.R. The NOIR CITY festival in San Francisco has been such a huge success. What do you attribute this to? Are you still looking at taking this festival on the road and can you give us a peek at what’s on tap for January 2006?

E.M. The biggest factor in the festival’s success is the movie going audience in the San Francisco Bay Area. They will leave their homes, cross town — or even a bridge — and pay admission to see a 60 year-old film. They’re the best. Taking it on the road will be a case-by-case thing. Programmers are territorial, and they like to do it themselves — as in Portland, where the museum up there copped our name and ran a NOIR CITY festival in March, showing a lot of titles we’d unearthed in previous festivals. That’s alright, because it’s important that these films make money. I’m just going to have to crack down on anybody using the NOIR CITY name, since it’s now synonymous with the Foundation; I don’t want to get blamed if one of these theaters ruins a print by building it up on a platter or something. It happens all the time, and its one reason why the studios are often hesitant about shipping old films to exhibitors.

A.R. Last question: How can someone contribute to the Film Noir Foundation?

E.M. Click here.